Author: David Wilber*

In the Hebrew Scriptures, the God of Israel commanded his people to observe the Sabbath (Exod. 20:8). Did the earliest followers of Jesus believe that this commandment remained binding on them? One way to approach this question is to observe how Jesus and his earliest followers lived with respect to the Sabbath.

The Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles contain numerous references to the Sabbath. This article examines these references to explore how Luke depicts the Sabbath practices of Jesus and his earliest followers. Through this examination, it becomes evident that from the beginning of Jesus’s ministry to the end of Acts, Luke consistently situates Jesus and his followers within Judaism by portraying them as Sabbath observant. Luke’s account underscores the importance of Sabbath observance in the lives of the earliest followers of Jesus, challenging the notion that they considered the Sabbath to be no longer binding.

Jesus’s Sabbath Custom

Luke first references the Sabbath at the beginning of Jesus’s public ministry. Following his baptism and the testing in the wilderness (Lk. 3:21-22; 4:1-13), Luke’s Jesus returns to Galilee and begins teaching in the synagogues (Lk. 4:14-15). Upon arriving in Nazareth, Luke records that Jesus went to the synagogue on the Sabbath day, “as was his custom” (Lk. 4:16).

The expression κατὰ τὸ εἰωθὸς (“as was his custom”) in Luke 4:16 is significant. Luke uses similar wording in other instances to express habitual practice (e.g., Lk. 2:42; Acts 17:2). The use of this expression indicates that Luke’s Jesus, like other religious Jews of his time, regularly attends and participates in the synagogue services on the Sabbath day.[1] According to Joseph Fitzmyer, by emphasizing Jesus’s “habitual frequenting of the synagogue,” Luke presents Jesus as “conforming to the general Jewish custom described by Josephus (Ant.16.2,4 § 43) of giving ‘every seventh day over to the study of our customs and law.’”[2] Hence, this passage illustrates Luke’s intent to depict Jesus as a faithful, Sabbath-observant Jew. In Luke’s account, Jesus upheld this Sabbath custom consistently throughout his life (Lk. 4:31; 6:6; 13:10).[3]

Some interpreters reject the notion that Luke aims to highlight Jesus’s commitment to Sabbath observance in Luke 4:16. For instance, Max Turner argues that Luke is focused more on highlighting Jesus’s “teaching rather than his Sabbath keeping” and that this verse “provides little real evidence of theological commitment on behalf of Jesus…to Sabbath worship.”[4] Yong-Eui Yang echoes Turner, suggesting that Jesus’s custom should not be viewed as a reflection of his devotion to Sabbath observance but merely as him seizing a convenient opportunity to teach the Jews.[5] Oliver, on the other hand, describes the narrow reading put forward by Turner and Yang as an “anachronistic missiological projection” and insists that the theological significance of Jesus’s Sabbath observance should not be dismissed.[6] For instance, as Oliver points out, “the preposition κατὰ followed by a noun in the accusative, frequently appears in Luke-Acts in contexts that have nothing to do with missionary activity but emphasize the fidelity of Jesus and his followers to Jewish custom.”[7] According to Oliver, it would seem that the narrow reading proposed by Turner and Yang fails to “do justice to the wider theological concern of Luke to depict Jesus, Peter, Paul, and his other central Jewish protagonists as faithful Torah observant Jews.”[8] Indeed, throughout Luke-Acts, Luke consistently emphasizes Jesus’s and the apostles’ commitment to the Law of Moses, the Jerusalem temple, the Sabbath, Jewish festivals, etc.[9] As Oliver writes, “Luke’s wider portrait makes it clear that his Jewish protagonists are not simply masquerading as Jews to gain converts, but observing Torah in its own right.”[10] Thus, considering the broader context of Luke-Acts, there is strong justification for viewing Luke 4:16 as yet another example of the author underscoring Jesus’s Torah observance—in this case, his regard for the Sabbath in particular—as a significant element of his theological practice.

Jesus’s Sabbath Conflicts

Although Luke presents Jesus as consistently observing the Sabbath, he also depicts him being accused of repeatedly violating it. For instance, in Luke 6:1-5, the Pharisees accuse Jesus of “doing what is not lawful to do on the Sabbath” after witnessing his disciples pluck heads of grain. In three additional passages, Jesus faces criticism from the religious leaders for performing healings on the Sabbath (Lk. 6:6-11; 13:10-17; 14:1-6). Some interpreters see these conflicts as evidence that Luke’s Jesus abrogated the Torah’s Sabbath laws.[11] However, there are at least four reasons why this interpretation is implausible.

First, Luke’s Jesus affirms the ongoing authority of the whole Torah, declaring that nothing from the Law of Moses is void as long as heaven and earth exist (Lk. 6:17; cf. Matt. 5:18). As Michael Wolter writes, “Luke has him maintain that the Torah is still valid without the smallest qualification.”[12] Given this deep respect for the Torah’s validity in all its details, it stands to reason that Luke’s Jesus upholds the Torah’s commandments about Sabbath observance.[13] Therefore, interpreting the Sabbath conflicts in Luke’s Gospel as evidence that Jesus intended to nullify the Sabbath contradicts the clear respect for the Torah’s authority expressed by Luke’s Jesus.

Second, the Law of Moses does not prohibit either the plucking of grain or healing on the Sabbath. Although some Jews in Jesus’s time interpreted the Torah to forbid these activities, such a reading is not supported by the Torah itself. Regarding the plucking of grain, the Pharisees seem to have considered the disciples’ actions to be a violation of the prohibition in Exodus 34:21 against “reaping” on the Sabbath.[14] However, Deuteronomy 23:25 explicitly distinguishes between full-scale harvesting and casually plucking grain by hand while passing through a field.[15] Hence, contrary to the Pharisees, the disciples’ actions do not fit within the Torah’s definition of “reaping” and therefore do not violate the prohibition in Exodus 34:21. Similarly, although some Jews during Jesus’s time viewed the healing of non-life-threatening conditions as a transgression of the Sabbath,[16] the Torah contains no such prohibition. Although Jesus and his disciples disregarded the misinterpretations and extrabiblical rules established by the religious leaders of their time, their actions do not constitute a transgression of the Sabbath laws established in the Law of Moses.[17]

Third, when Jesus was confronted about his behavior on the Sabbath in Luke’s narrative, he did not claim that he and his disciples had the right to disregard the Sabbath. Instead, he defended his and his disciples’ Sabbath activities as “lawful” (Lk. 6:9; 14:3).[18] In each dispute, he makes a legal case for why their actions were permissible and why their opponents’ accusations were baseless.[19] This response from Jesus is the opposite of what one would expect if Luke intended these passages to indicate that Jesus abrogated the Sabbath. Conversely, such a response is precisely what one would expect if Luke intended to emphasize Jesus’s and his disciples’ commitment to upholding the sanctity of the Sabbath.[20]

Fourth, it is noteworthy that in the book of Acts, Luke mentions no conflicts between the apostles and religious leaders regarding Sabbath observance.[21] Instead, Luke emphasizes that the apostles frequently attended synagogue services on the Sabbath (Acts 13:14; 16:13; 17:2; 18:4), following the established custom of Jesus (Luke 4:16). This account in Acts is surprising if Luke intended these conflict passages to indicate that Jesus had nullified the Sabbath for his followers. As Benjamin Frostad notes, “If Luke had intended Jesus’ Sabbath controversies to serve as a precedent for his followers to disregard the Sabbath, the absence of any polemics surrounding Sabbath observance in Acts is striking.”[22]

In light of these considerations, it is inappropriate to interpret these “conflict passages” as instances of Jesus challenging the Sabbath’s validity. Instead, interpreters should understand these passages within Judaism—as dialogues between Jesus and his fellow Jewish leaders regarding the proper way to observe the Sabbath. Although Jesus opposed the interpretations of other Jewish teachers in his time, he did not oppose the Sabbath commandment in principle. Rather, according to Luke, Jesus was deeply concerned with proving how his Sabbath activities were “lawful.” This evidence is entirely consistent with the idea that Jesus considered the Sabbath binding.

Sabbath Observance Among Jewish Followers of Jesus

After recounting how Jesus himself faithfully observed the Sabbath, Luke describes how Jesus’s Jewish followers continued to observe it as well. Notably, after Jesus’s crucifixion, Luke records that the women who followed Jesus “rested [on the Sabbath] according to the commandment” (Lk. 23:56), postponing their plans to anoint his body until the Sabbath was over. According to Oliver, Luke’s mention of the women’s obedience “highlights his eagerness to illustrate that the Jewish followers of Jesus remain faithful in their observance of the Sabbath and the Torah in general.”[23] This continued emphasis on prioritizing the Sabbath even after Jesus’s crucifixion is surprising if his earliest Jewish followers believed his coming nullified the commandment, but it aligns precisely with what one would expect if they believed that the commandment remained in effect.

In Acts 1:12, Luke’s passing reference to “a Sabbath day’s journey” may provide further insight into the ongoing relevance of Sabbath observance for Luke and the early Jewish followers of Jesus. While some interpreters downplay the significance of this reference,[24] others insist it has “theological importance.”[25] According to Craig Keener, “Luke mentions the Sabbath day’s journey to show their proximity to the holy city (fulfilling Luke 24:49) but also to indicate that they continued to observe the law (cf. 23:54-56).”[26] Fitzmyer similarly argues, “Luke is concerned with depicting the apostles as Christians who are still observant of their Jewish obligations.”[27] At the very least, Luke’s reference to the Sabbath travel limits in Acts 1:12 shows that his “characters and narrative are firmly located in a world of Torah observance.”[28]

Additionally, Luke repeatedly references the Sabbath in connection with Paul’s ministry throughout Acts.[29] In Acts 13, Paul and Barnabas attend and teach in the synagogue in Pisidian Antioch on consecutive Sabbaths (Acts 13:14, 27, 42, 44). Similarly, Luke notes that Paul goes to the river outside Philippi to pray on the Sabbath (Acts 16:13) and repeatedly participates in synagogue services on the Sabbath in both Thessalonica (Acts 17:2) and Corinth (Acts 18:4). Some interpreters attempt to discount these references, suggesting that Paul’s Sabbath custom was merely a missionary strategy to reach Jews with the gospel.[30] However, according to Oliver, such a “reductionistic reading” is a “mistake” and “unlikely given the absence in Acts of any negative statement about the Sabbath and its observance.”[31] While it is true that Paul used these occasions to share the good news of the Messiah, it is important to remember that what is now called “Christianity” was not yet a distinct religion from Judaism at that time. The first Christians saw their movement as a sect within Judaism called the “sect of Nazarenes” (Acts 24:5). The word αἵρεσις (“sect”) is the same word used to describe the Pharisees and Sadducees (Acts 5:17; 15:5), which were both considered part of first-century Judaism. Hence, Paul’s intention was not to infiltrate the synagogue to pull people away from Judaism. He and his ministry colleagues were religious Jews who worshiped in the synagogue on the Sabbath.[32]

In sum, according to Luke, the early Jewish followers of Jesus continued to keep the Sabbath. By drawing attention to the women who rested on the Sabbath after Jesus’s death, the Sabbath travel limits, and Paul’s customary Sabbath worship, Luke emphasizes these early believers’ commitment to Sabbath observance. These findings are consistent with the notion that the earliest Jewish followers of Jesus considered the Sabbath commandment binding, and they seem quite inconsistent with the notion that they thought Jesus’s coming nullified this commandment.

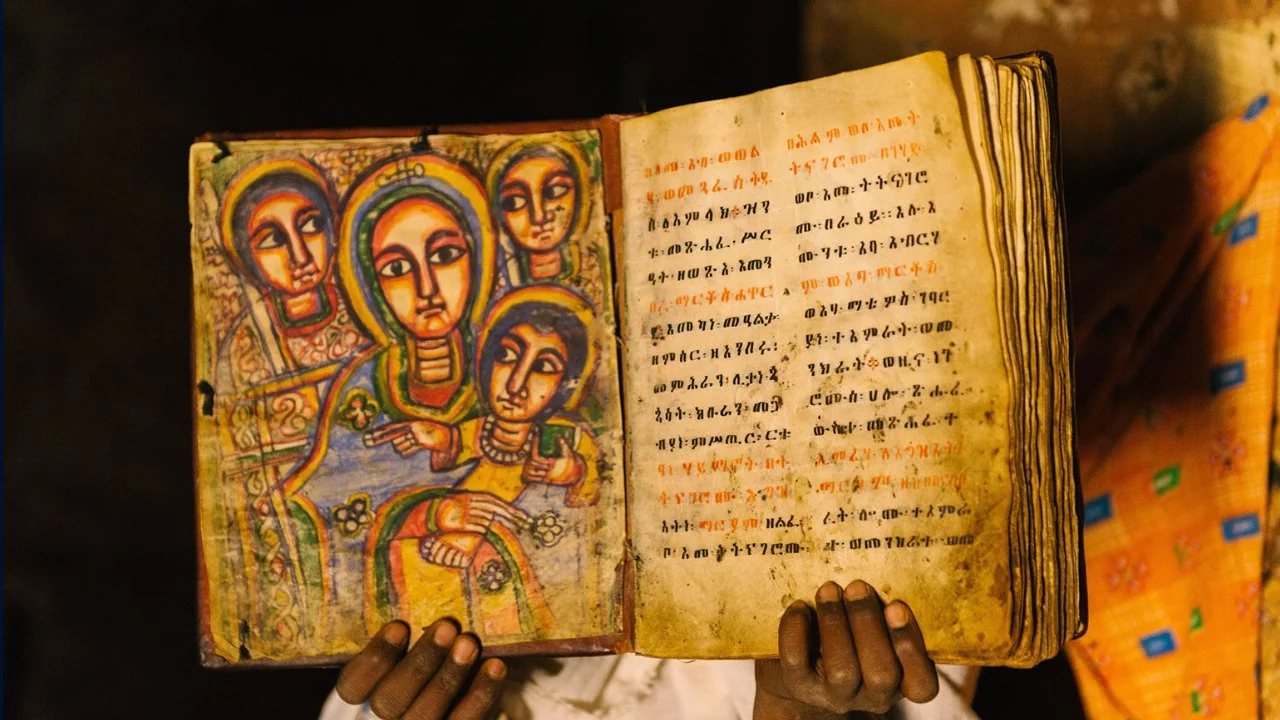

Sabbath Observance Among Gentile Followers of Jesus

Throughout the Book of Acts, Luke consistently portrays Jewish followers of Jesus as faithfully resting and worshiping on the Sabbath, indicating that Sabbath observance remained standard practice among Jewish believers in Jesus. However, the question remains whether Jesus and the apostles also expected Gentile believers to keep the Sabbath. Certain passages in Acts suggest that Luke may indeed have regarded Sabbath observance as meaningful for Gentile believers as well.

In the book of Acts, Luke frequently depicts Gentiles participating in synagogue services and hearing the Torah read on the Sabbath (Acts 13:14-16, 26, 43-45, 48; 14:1; 17:1-4; 18:4). These Gentiles, who were already gathering alongside Jews on the Sabbath, represent a significant number of those who come to faith in Jesus throughout the book of Acts.[33] Luke seems to assume that these Gentile believers in Jesus, who were already participating in synagogue services on the Sabbath, would continue doing so.[34] This expectation is reinforced in the Jerusalem Council discussion on whether Gentile believers in Jesus needed to get circumcised to be “saved” and fully integrated into the Christian community (Acts 15:1, 5).[35] In agreement with the Law of Moses, which does not mandate circumcision for adult Gentiles,[36] the apostles concluded that circumcision was not required of the adult Gentile believers in Jesus. However, this decision did not imply that Gentile believers were exempt from obeying the commandments in the Torah that applied to them as Gentiles. As William Willimon observes, “Nowhere does Luke suggest that Jesus abrogates the Torah. Even gentiles are to keep that part of the Torah which applies to them as non-Jews.”[37] Hence, James determined that the Gentile believers should initially adhere to four commandments from the Law of Moses as a starting point for fellowship (Acts 15:19-20; cf. Exod. 34:15; Lev. 17:10-16; 18:6-23).[38] He then anticipated that they would learn the other commandments that applied to them by attending synagogue services, where the Law of Moses was read and taught every Sabbath (Acts 15:21). Therefore, in Acts 15:21, Luke attributes to James the expectation that Gentiles who come to faith in Jesus would join Jewish believers in observing the Sabbath in the synagogues, where they would receive instruction in Moses’s teachings. As Benjamin Frostad writes, “James’s proposal assumes that Gentile believers will have an ongoing relationship with the (believing) Jewish community, that their lives will be structured around the biblical calendar, and that they will grow in their knowledge and observance of Scripture.”[39]

Sunday Observance in Acts

A potential challenge to the thesis of this article appears in Acts 20:7, where Luke records that believers met “on the first day of the week” to break bread and hear Paul’s teaching. Some interpreters view this verse as evidence that Sunday worship had begun to replace the customary Sabbath gatherings among early followers of Jesus.[40] However, this proposal seems implausible for at least two reasons.

First, the notion that Acts 20:7 reflects a recurring practice goes beyond the evidence. While it is possible that Luke is referring to a regular weekly meeting, it is equally possible that he is describing a one-time occasion.[41] The text simply states that Paul was “intending to depart on the next day,” which suggests that these believers may have gathered specifically to learn from him before he left. As Graham Twelftree writes, “It cannot be concluded that the meeting (probably of believers, cf. Acts 20:2) said to take place on ‘the first day of the week’ is, for Luke, a distinctive Sunday worship event, for this is the only time Luke mentions this phrase and it seems to have no particular significance.”[42] Some might argue that the mention of breaking bread is a reference to the Lord’s Supper, implying that this was a regular worship service. But even if one assumes that this is a reference to the Lord’s Supper, that still does not mean that Acts 20:7 represents a distinct weekly meeting since Luke elsewhere (cf. Acts 2:46) states that the early believers “broke bread” every day.[43]

Second, even if one grants that Acts 20:7 points to a pattern of weekly Sunday gatherings, this still does not suggest that the earliest believers in Jesus had ceased observing the Sabbath on the seventh day. As noted above, Luke consistently portrays the earliest followers of Jesus to have continued to keep the Sabbath. At most, then, Acts 20:7 may suggest that some first-century believers regularly observed both days.[44] Historians suggest that the shift from Sabbath observance to exclusive Sunday worship among Christians was a development that occurred significantly later in history.[45]

In sum, Acts 20:7 does not support the conclusion that the early believers replaced Sabbath observance with Sunday gatherings. The meeting on the first day of the week may have been a one-time event arranged due to Paul’s imminent departure. Furthermore, even if Acts 20:7 is interpreted to suggest that Sunday gatherings were customary, it does not follow that the early Christians had abandoned Sabbath observance. As Frostad observes, “If Luke had intended to communicate to his readers either that the Sabbath had been abolished or that it had changed from Saturday to Sunday, one would expect that theme to be more developed in his narrative rather than confined to one obscure event.”[46]

Conclusions and Implications

This study has shown that Luke consistently portrays Sabbath observance as central to the religious lives of Jesus, his Jewish followers, and even Gentile believers. Contrary to the notion that the earliest Christians abandoned the Sabbath, Luke’s Gospel and Acts affirm that Sabbath worship remained standard practice within the early Christian movement. Luke’s emphasis on the Sabbath practices of Jesus and his followers reflects continuity with the Hebrew scriptures and Second-Temple Judaism.

It is acknowledged that references to Jesus and the earliest Christians keeping the Sabbath do not necessarily prove that Christians today should continue this practice. These references are descriptive rather than prescriptive—they describe what Jesus, the apostles, and the earliest Christians did, but they do not explicitly prescribe Sabbath observance for Christians today. However, it may be worth considering that the Hebrew Scriptures do prescribe Sabbath observance, and the key question is whether that commandment changed with the coming of Jesus. As this study has demonstrated, Luke’s account is entirely inconsistent with the idea that anything changed regarding the Sabbath. On the contrary, Jesus and his followers acted as though the command to keep the Sabbath remained in effect. Consequently, these findings invite followers of Jesus today to reflect on the relevance of Sabbath observance in their own lives.

* This article was first published in the E-Journal of Religious and Theological Studies, 11 no.3 (2025): 51–59. See the orignal article here.

[1] Isaac W. Oliver, Torah Praxis after 70 CE: Reading Matthew and Luke-Acts as Jewish Texts, WUNT II 355 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2013, 70. Oliver cites Luke 2:42 (“And when he was twelve years old, they went up as usual [κατὰ τὸ ἔθος] for the festival”) and Acts 17:2 (“And Paul went in, as was his custom [κατὰ δὲ τὸ εἰωθὸς], and on three sabbath days argued with them from the scriptures”). See also Mark S. Kinzer, Jerusalem Crucified, Jerusalem Risen: The Resurrected Messiah, the Jewish People, and the Land of Promise (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2018), 179–183.

[2] Joseph A. Fitzmyer, The Gospel according to Luke, AYBC 28A (Garden City, NY: Doubleday 1981), 1:530.

[3] See Kinzer, Jerusalem Crucified, 174: “Luke stresses that Jesus made a habit of worshipping in the synagogue on the Sabbath. Since this habitual behavior is noted in reference to his conduct in ‘Nazareth, where he had been brought up,’ readers are to presume that such Sabbath observance characterized the entirety of Jesus’ life, both before and after his baptism.”

[4] Max M. B. Turner, “The Sabbath, Sunday, and the Law in Luke/Acts,” in From Sabbath to Lord’s Day, ed. D. A. Carson (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1982), 102.

[5] See Yong-Eui Yang: “Jesus visited the synagogue on the sabbath in order to have teaching opportunities (that is, with practical purpose)” (Jesus and the Sabbath in Matthew’s Gospel, JSNTSup 139 [Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1997], 245).

[6] Oliver, Torah Praxis, 72–73.

[7] Ibid., 72. Oliver cites Luke 1:9; 2:2, 24, 27, 39, 42; 22:29; 23:56; Acts 17:2; 22:12; 26:5.

[8] Ibid., 73.

[9] Luke’s Jesus affirms the continued relevance of the Law of Moses (Lk. 16:17) and repeatedly emphasizes the value of knowing and obeying it (Lk. 10:25-28; 16:19-31; 18:18-30). He also depicts the apostles regularly engaging in temple worship (Lk. 24:53; Acts 2:46; 3:1; 5:42; 21:26; 24:17) and observing the Sabbath (Lk. 4:16, 31; 6:1–6; 13:10; 14:1; 23:54-56; Acts 13:14, 42, 44; 16:13; 17:2; 18:4) and Jewish festivals (Lk. 2:41-42; 22:1, 7; Acts 2:1; 18:21; 20:6, 16; 27:9). For further discussion on Luke’s focus on early Christian Torah observance, see Jacob Jervell, Luke and the People of God: A New Look at Luke-Acts (Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg Publishing, 1972), 133-151. See also David J. Rudolph, “Paul and the Torah According to Luke,” Kesher: A Journal of Messianic Judaism 14:1 (2002), 61-73.

[10] Oliver, Torah Praxis, 73.

[11] See Norval Geldenhuys: “In place of the old rigid Sabbath observance [Jesus] introduced the new spiritual Sabbath-rest…For this reason it is fit and proper that Christians should dedicate the first day of every new week to Him in a special sense; while it remains true that the Christian has not one holy day in the week, but seven” (Commentary on the Gospel of Luke, NICNT [Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1975], 200). See also Stephen G. Wilson: “Whatever other ramifications there may be in the assertion that Jesus is lord of the sabbath, one remains clear: it can be used to justify a rejection of current sabbath practice” (Luke and the Law [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983], 33–34).

[12] Michael Wolter, The Gospel according to Luke, vol. 2, trans. Wayne Coppins and Christoph Heilig (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2017), 276.

[13] See Graham H. Twelftree: “Luke’s Gospel depicts the Law as good and of ongoing significance for his readers…[I]n the disputes about the Sabbath, Luke is concerned to show that Jesus acted in complete accord with the Law” (People of the Spirit: Exploring Luke’s View of the Church [Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2009], 54).

[14] The rabbinic literature identifies thirty-nine categories of prohibited “work” on the Sabbath, one of which is “reaping” (m.Shabbat 7.2). According to Matthew Thiessen, “The rabbis flesh out what this category of work entails in the Tosefta—it includes the plucking of grain as a subset of reaping” (Jesus and the Forces of Death: The Gospels’ Portrayal of Ritual Impurity Within First-Century Judaism [Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2020], 156. Thiessen cites Tosefta, Shabbat 9.17).

[15] See also Exod. 23:10-11 and Lev. 25:5-6, 11-12, where the Torah permits gleaning from the fields during the Sabbatical year but forbids “reaping.”

[16] Darrell L. Bock, Luke, NIVAC (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1996), 179. Bock cites m.Yoma 8.6.

[17] David Wilber, Remember the Sabbath: What the New Testament Says About Sabbath Observance for Christians (Clover, SC: Pronomian Publishing, 2022), 35-48; 164-169.

[18] According to Joshua P. Smith and Matthew Thiessen, “Some Pharisees wonder why Jesus’s disciples pluck grains on the Sabbath, but Jesus provides a legal defense of their actions (Luke 6:1–5). And three times Jesus heals the sick on the Sabbath, engendering criticism. Again, Jesus does not respond by rejecting the Sabbath, but by making a legal argumentation for why it is appropriate and acceptable for him to do so (6:6–11; 13:10–17; 14:1–6): for Luke’s Jesus, the Sabbath is an ideal time to provide healing and relief and rest for those laboring from illness” (“Luke Within Judaism” in Within Judaism? Interpretive Trajectories in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam from the First to the Twenty-First Century, ed. Karin Hedner Zetterholm and Anders Runesson [Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2024], 144).

[19] See Jervell, Luke, 140: “There is no conflict with the law in Jesus’ attitude as described in many disputes about the Sabbath. Luke records no less than four disputes, and he is concerned to show that Jesus acted in complete accordance with the law, and that the Jewish leaders were not able to raise any objections.” Also note that in Matthew’s account of the grainfield conflict, Jesus explicitly claims that his opponents are condemning the “guiltless” (Matt. 12:7).

[20] See Oliver, Torah Praxis, 146: “Luke reports more Sabbath healings than any other author but never presents in these episodes a presumptuous Jesus who stands aloof from halakic and Jewish sensibilities, sweepingly announcing the abolition of a central commandment of the Torah. Instead, Luke, like Matthew, combines eschatological-christological statements with halakic-ethical considerations in order to bolster Jesus’ Sabbath praxis in ways that comply with the ethos of the Torah and imply its ongoing relevance for Jewish followers of Jesus.”

[21] See Ibid., 211: “as the narration gradually shifts from the persona of Jesus in the gospel of Luke to his followers in Acts, polemics regarding Sabbath practice completely disappear.”

[22] Benjamin Frostad, “He Made No Distinction: Gentiles and the Role of Torah in Acts 15” (MA Thesis, Briercrest Seminary, 2021), 69.

[23] Oliver, Torah Praxis, 163. See also William R.G. Loader: “Luke alone, among the evangelists, makes a point of emphasising their Torah observance (23:56). It is as relevant to emphasise this at the end of Jesus’ life as it was at it the beginning, because obedience to Torah and sharing Israel’s hopes are fundamental values which Luke’s Jesus and Luke assume” (Jesus’ Attitude towards the Law, WUNT II 97 [Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1997], 357).

[24] See Turner, “The Sabbath, Sunday, and the Law in Luke/Acts,” 124: “From 1:12 we may deduce nothing about early church Sabbath theology and little more about their Sabbath practice.”

[25] Martin Hengel, “The Geography of Palestine in Acts,” in The Book of Acts in Its First Century Setting, vol. 4: Palestinian Setting, ed. Richard Bauckham (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1995), 47.

[26] Craig S. Keener, Acts: An Exegetical Commentary, vol. 1 (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2012), 735.

[27] Joseph A. Fitzmyer, The Acts of the Apostles (New York, NY: Doubleday, 1998), 213.

[28] Richard I. Pervo, Acts: A Commentary, Hermeneia (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2009), 46.

[29] See Oliver, Torah Praxis, 234: “Like Luke’s Jesus (Luke 4:16–30; cf. Luke 4:31), the Paul of Acts enters synagogue space on a regular basis each Sabbath in order to proclaim the good news allegedly announced in the Jewish scriptures (Acts 13:14, 27, 42, 44; 15:21; 16:13; 17:2; 18:4).”

[30] See Arthur G. Patzia: “Contacts with the synagogue…were important in Paul’s missionary activity only as opportunities to initiate the proclamation of the gospel” (The Emergence of the Church: Context, Growth, Leadership and Worship [Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2001], 187).

[31] Oliver, Torah Praxis, 238.

[32] See Denis Fortin: “Paul’s visits to synagogues on Sabbath are not merely a strategy to win converts. Paul can be seen as a faithful Jew and observing the Sabbath: at this point in early Christian history, Paul and his colleagues are Jewish believers in Jesus the Messiah and keep the Sabbath” (“Paul’s Observance of the Sabbath in Acts of the Apostles as a Marker of Continuity Between Judaism and Early Christianity,” AUSS 40, no. 2 [2015], 329).

[33] See Jervell, Luke, 44: “The references to the conversion of Gentiles speak mainly of ‘God-fearing’ Gentiles, who already are related to Israel and Judaism via the synagogue, though without being circumcised (13:43; 14:1; 17:4, 12). The passages show that Jewish and Gentile conversions have been so combined that both groups accept the gospel together.” There are, however, some exceptions to this pattern. See Acts 14:9; 16:25-34; 17:34.See Jervell, Luke, 44: “The references to the conversion of Gentiles speak mainly of ‘God-fearing’ Gentiles, who already are related to Israel and Judaism via the synagogue, though without being circumcised (13:43; 14:1; 17:4, 12). The passages show that Jewish and Gentile conversions have been so combined that both groups accept the gospel together.” There are, however, some exceptions to this pattern. See Acts 14:9; 16:25-34; 17:34.

[34] A potential objection to this assumption is Acts 18:6-7, where it might seem that Luke depicts Paul as rejecting the Jews and the synagogue and starting a separate Gentile church. However, Bart J. Koet observes, “Although Paul leaves Corinth’s synagogue, he remains in the same (spiritual) sphere.” As Koet goes on to point out, the Corinthian house church was right next door to the synagogue (Acts 18:7). Moreover, the ruler of that synagogue was also a founding member of the Corinthian house church (Acts 18:7- 8; 1 Cor. 1:14). This suggests that the Corinthian Christians remained connected to the Corinthian Jews. As Koet writes: “We see that Paul stays in the confines and thus in the realm of the synagogue. Luke even says that in a very symbolic way: Paul went to the house which is next door to the synagogue; in fact he says it even more precisely: having a common wall with the same synagogue (συνομοροῦσα). The fact that Luke shows that Paul remains spatially as near to the synagogue as possible is more or less a metaphor for his being as closely connected to the synagogue as can be and that thus Luke makes a point about Paul’s desire for a continuing relation to Jews” (“As Close to the Synagogue as Can Be: Paul in Corinth (Acts 18.1-18),” in The Corinthian Correspondence, ed. R. Bieringer [Leuven: Leuven University Press, 1996], 408-409).

[35] As Markus Bockmuehl explains, “verse 1 clearly defines the question as being about what Gentiles must do to be saved. The maximalist case was being advanced by Christian Pharisees who argued…that covenant membership requires full conversion” (Jewish Law in Gentile Churches: Halakhah and the Beginning of Christian Public Ethics [New York, NY: T&T Clark, 2000], 164).

[36] Leviticus 12:3 emphasizes the duty of Israelite parents to circumcise their male infants on the eighth day of birth; it says nothing about whether adult Gentiles must get circumcised. Moreover, Genesis 17:10-14 specifically states that the commandment of circumcision is given to Abraham and his offspring, starting with Isaac (Gen. 17:19), and that the command is to be carried out on the eighth day of birth (Gen. 17:12), as Isaac’s example proves (Gen. 21:4). The law in Genesis 17 does also require that Abraham’s household circumcise their slaves, but there is no commandment in the text for adult Gentiles who might join the community to undergo circumcision. One might point to Exodus 12:44-49 as counterevidence to the notion that the commandment of circumcision does not apply to adult Gentiles. However, this passage only prohibits uncircumcised adult Gentiles (and native Israelites; see Exod. 12:49 and Josh. 5) from eating the sacrificial meat of the Passover meal. If an adult Gentile wants to eat the Passover lamb, he must get circumcised. However, it is important to notice that this passage is not a general commandment for adult Gentiles to get circumcised. While they cannot eat the Passover lamb, uncircumcised adult Gentiles who follow the God of Israel are still part of the faith community in every other context. For more on this, see Frostad, “He Made No Distinction,” 16-20. See also David Wilber, How Jesus Fulfilled the Law: A Pronomian Pocket Guide to Matthew 5:17-20 (Clover, SC: Pronomian Publishing, 2024), 59-70.

[37] William H. Willimon, Acts, IBC (Atlanta, GA: John Knox Press, 1988), 131.

[38] See Frostad, “He Made No Distinction,” 75: “The four prohibitions demarcate the minimum, not the maximum, for Gentile believers to observe. They represent a starting point from which new believers were expected to grow.”

[39] Ibid., 112. See also Eyal Regev: “The implications [of Acts 15:21] are that since the Torah is proclaimed and studied in the synagogue on a regular basis, the God-fearing Christians would gain further knowledge and adhere to Jewish law after being accepted into the (Jewish-) Christian community. The legal obligations of the Apostolic Decree may have been an invitation to observe Jewish law” (“The Gradual Conversion of Gentiles in Acts and Luke’s Paradox of the Gentile Mission,” in Law and Narrative in the Bible and in Neighbouring Ancient Cultures, ed. F. Avemarie and K. P. Adams [Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2012], 361).

[40] See Yang, Jesus and the Sabbath in Matthew’s Gospel, 260, who hesitatingly concludes that “sabbath observance was no longer a real issue for Luke and his readers, who may already quite possibly have kept Sunday as the day of worship (cf. Acts 20.7).” Craig Blomberg is more confident in this conclusion. Citing Acts 20:7, Blomberg writes, “already in the first century, some Christians transferred their day of worship from Saturday to Sunday, the day of Jesus’ resurrection” (“The Sabbath as Fulfilled in Christ,” in Perspectives on the Sabbath: 4 Views, ed. Christopher J. Donato [Nashville, TN: B&H Academic, 2011], 308).

[41] See Craig Keener: “Luke’s note that the church was meeting on the first day could indicate a regular practice, or it could point to a practice that was unusual” (Acts: An Exegetical Commentary, vol. 3 [Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2014], 2963).

[42] Twelftree, People of the Spirit, 137.

[43] Robert K. McIver, “When, where, and why did the change from Sabbath to Sunday worship take place in the early church?” AUSS 53, no 1 (2015), 21-22.

[44] Evidence from the fourth and fifth centuries AD shows that Christians widely worshiped on both the Sabbath and Sunday (See, e.g., Socrates Scholasticus, Ecclesiastical History 5.22; Sozomen, Ecclesiastical History 7.19), so it is possible that such dual-observance may have been present among first-century believers as well.

[45] Justo González, A Brief History of Sunday: From the New Testament to the New Creation (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2017), chap. 1-2.

[46] Frostad, “He Made No Distinction,” 70.

About David Wilber

David Wilber is an author, Bible teacher, and CEO of Pronomian Publishing LLC. He has written several books and numerous theological articles, with his work appearing in outlets such as the Christian Post and the Journal of Biblical Theology. David has spoken at churches and conferences across the nation and has served as a researcher and Bible teacher for a number of Messianic and Christian ministries…