Author: David Wilber

A popular Internet blogger by the name of Jim Staley recently claimed that the pseudepigraphical book known as Jubilees “was at one time considered Holy Scripture by many of the early Jews and Christians.”[1] Staley cited no source for this claim but simply threw it out there like it was a commonly accepted fact.

Since this article was posted publicly on Facebook, I left a public comment asking for a source to back up Staley’s claim. In addition, I shared some historical information that appears to be in conflict with his assertion. I am pleased that Staley took the time to address my concerns directly in an article titled “Public Challenge.”[2] Below is my response.

Before I deal with the points he raised in his article, let me quickly state and defend my contention: The Judaisms of the Second Temple era—including Christians—did not consider the pseudepigrapha (such as Jubilees, 1 Enoch, etc.) to be “Scripture.”

I will make four points in support of this contention. First, the books that make up the Tanakh are referred to in the New Testament and other Second Temple era Jewish literature as the Torah, Nevi’im, and Ketuvim—that is, the Law, the Prophets, and the Psalms. This threefold “canon” of Scripture even appears in the New Testament. For instance, in Luke 24:44-45, Yeshua makes direct reference to this threefold canon and defines it as “the Scriptures.” This means that Yeshua the Messiah gave this canon divine affirmation as the Scriptures.

Second, this threefold designation was used to define the canon of Scripture long before the time of Yeshua and the apostles. For instance, Ben Sira, the author of the Apocryphal book, the Wisdom of Sirach, or Ecclesiasticus, had a grandson who translated his grandfather’s writings into Greek around 130 BCE. This translator wrote his own prologue to the translation, which makes reference to the threefold shape of the Old Testament canon.

In regard to this prologue, Scholar Roger T. Beckwith writes:

It appears, then, that for this writer there are three groups of books which have a unique authority, and that his grandfather wrote only after gaining great familiarity with them, as their interpreter not as their rival. The translator explicitly distinguishes ‘these things’ (i.e. Ecclesiasticus, or uncanonical Hebrew compositions such as Ecclesiasticus) from ‘the Law itself and the Prophecies and the rest of the Books’ […] And not only does he state that in his own day there was this threefold canon, distinguished from all other writings, in which even the Hagiographa formed a closed collection of old books, but he implies that such was the case in his grandfather’s time also.[3]

Thus, by the time this prologue to the Wisdom of Sirach was written, which was around 130 BCE, this idea of a closed canon of Scripture already existed. The books contained in this canon were already widely considered to be uniquely sacred and distinct from any additional writings, such as the apocryphal writings.

As far as we know, no manuscript or historical evidence indicates that the pseudepigraphical literature, such as 1 Enoch or Jubilees, was ever accepted as part of this threefold canon of Scripture. Neither the Greek Septuagint nor the Hebrew Masoretic texts included the pseudepigrapha in their sets. This evidence would entail that the threefold canon of the Hebrew Scriptures, which was divinely affirmed by the Messiah, excluded the Pseudepigrapha.

Third, in a passage from Against Apion, written in the 90s CE, the first-century Jewish historian Josephus wrote that a defined Hebrew canon already existed by his time.[4] Once again, Josephus acknowledges this threefold canon of the Hebrew Scriptures—the same that we find in the gospel of Luke and other early Jewish literature. What’s perhaps most interesting about this passage is that Josephus limits these inspired books to a certain number: twenty-two.[5] Five books, he says, are the books of Moses. 13 are the prophets. And the remaining 4 he says are hymns to God and precepts for human life.

This is significant evidence from a primary source that, by the 90s CE, a specific number of books were already considered to be uniquely authoritative. And, according to Josephus, all Jews accepted this. The Jewish canon today has 24 books, which matches the contents of our protestant canon of 39 books. The reason for the difference in number is that the Jewish canon combines books that are separated in the protestant canon—for example, in the Jewish canon, all the Minor Prophets are combined into one book. Josephus’ canon is believed to have also combined Ruth with Judges and Lamentations with Jeremiah, which are separated in the current Jewish canon, giving us a twenty-two book canon.

In either case, no scholar believes that any book that isn’t already part of the Old Testament canon we have today would have been part of this Josephus’ first century canon. Thus, the canon of the Jewish people, according to Josephus, excluded the pseudepigrapha.

Fourth, not even the Qumran community, which certainly revered books like 1 Enoch and Jubilees, included this literature in their canon. Beckwith writes:

The use by the Therapeutae or the Essens of the standard three divisions of the canon, and of one of the standard counts of the canonical books, and their grouping of their own pseudepigrapha in a separate appendix, imply that the three sections and the standard count were already agreed and settled among the Jews before the Essenes separated from the rest about 152 BC. Three of the books of 1 Enoch had been written by that time, but the Essenes had evidently not attempted to include them in any of the three sections of the canon, or to number them in the count of the canonical books, since they did nothing of the kind after the separation, either with these pseudepigrapha or subsequent pseudepigrapha.[6]

In conclusion:

Among the Judaisms of the second temple era, a threefold canon of Scripture was widely considered to be uniquely sacred and authoritative.

According to the evidence, pseudepigraphacal literature, such as 1 Enoch and Jubilees, has never been considered part of this threefold canon of the Hebrew Scriptures. Not even fringe sects, such as the Qumran community, who held these writings in high regard, considered them Scripture.

Yeshua the Messiah gave this canon, which excluded this literature, divine affirmation as the Scriptures. Since we know what writings the Jews considered canonical, and we know that Yeshua referred to those writings using the standard Jewish terminology of the canon without ever disputing the contents, we have every reason to conclude that Yeshua was in complete agreement with the Judaisms of His day in regard to the extent of the canon. Thus, Messiah’s definition of Scripture excludes the pseudepigrapha.

All of this entails that neither the early Jews nor the early followers of Yeshua (Christians) of the Second Temple era considered the pseudepigrapha to be Scripture.

Answering Objections

I will now address the points Staley raised in the article mentioned above.

First, Staley prefaces his article with a few paragraphs saying that he feels it is unchristlike and unloving to publicly challenge others on their public statements. He writes on how love is the greatest commandment and how it is important to display the fruit of the Spirit in everything we do.

Obviously I agree that love is the greatest commandment and that we must display the fruit of the Spirit, but publicly challenging other believers is not contrary to that. We know this because Yeshua and the apostles publicly challenged people throughout the New Testament. Believers are expected to correct those in error. As Paul teaches, this correction must be done in “gentleness,” but love still requires correction (2 Timothy 2:24-26). Can correction be handled wrongly and cause more harm than good? Of course. But if a public challenge to someone’s public statements is done without arrogance and in a spirit of love, then nothing is unchristlike about it. While I agree that love and the fruit of the Spirit are most important, unfortunately the introduction to Staley’s article seems a little manipulative. Now any public response to him, no matter how kind, will be perceived as unloving by virtue of it being a “public challenge.”

The second point I’d like to make at the outset is that this article was supposedly a defense of Staley’s original assertion that the pseudepigraphical book known as Jubilees “was at one time considered Holy Scripture by many of the early Jews and Christians.” Unfortunately, rather than defend his original assertion, Staley appears to be “moving the goal posts.” His arguments revolve around how early Christians and Jews read and revered the pseudepigraphical literature. Of course, that is not in dispute. But that does not entail that they considered these writings “Holy Scripture,” as he had originally stated.

Let’s go through the article point-by-point:

… although the Hebrew ‘canon’ was already in place by the time of Christ, there were many other Jewish works that were highly valued within Judaism and were quoted, read, studied and revered by many Jews and Christians. Even Jude quotes directly from 1 Enoch in his letter, proving that some NT authors considered at least parts of Apocryphal works authoritative in nature.

Again, his original statement was that the early Jews and Christians considered the pseudepigraphacal literature such as Jubilees to be “Scripture.” That’s the assertion I took issue with. I never disagreed that this literature was read and highly valued among the Second Temple Judaisms. But that fact does not mean that they considered this literature to be Scripture or even necessarily that they considered it religiously authoritative. Some fringe sects, like the Qumran community, did believe that some of the pseudepigrapha held religious significance, but, again, that does not entail that they thought of it as Scripture. More on this a little later.

A few things can be said regarding Jude’s “quote” of 1 Enoch (Jude 14-15; 1 Enoch 1:9; 60:8). First, it’s possible that Jude wasn’t quoting 1 Enoch but that he and the author of the similar passage from 1 Enoch were referencing the same oral tradition. That is to say, Jude wasn’t relying on the Enochic writings for this saying of Enoch. Rather, Jude and the author of that particular passage from 1 Enoch were relying on the widely held tradition of what the actual Enoch said. For instance, as Ryan White points out, Jude never mentions a book or scroll of Enoch, only what Enoch said.

Second, the passages aren’t exactly the same. White writes:

Jude states God will convict the ungodly while Enoch proclaims their destruction; a subtle yet vital difference. This passage in 1 Enoch is not actually something unique to the book itself either; it is a midrash on Deuteronomy 33:2-3 where YHWH is said to come with ‘the ten thousand holy ones.’ It is likely that this midrash was not limited to the Book of Enoch but was something discussed by various traditions at the time.[7]

However, even if Jude did directly quote from 1 Enoch, that still does not entail that he considered it Scripture or to have divine authority. The biblical authors quoted plenty of material that nobody would consider sacred or inspired of God. Semitic scholar, Dr. Michael Heiser, puts this point well:

Just as preachers today quote commentaries, journals, news periodicals, or even television shows to drive home or illustrate a point, so the biblical writers used external material to draw attention and make a statement. Paul quotes from pagan Greek poets. The psalmists and prophets borrow vocabulary and paraphrase material from ancient Egyptian, Mesopotamian, and Syrian literature. Jude quotes a book from the Pseudepigrapha (ancient writings that falsely claim authorship by a biblical character). The people of biblical times knew the quoted material wasn’t inspired, but it had meaning for them and their audience.[8]

In summary, nobody disagrees that the pseudepigrapha was read, quoted, and highly valued among the Second Temple Judaisms, including the early Christians. But that does not mean they considered this literature to be Scripture or to have divine authority.

After quoting James H. Charlesworth on the influence of 1 Enoch among the Second Temple Judaisms, Staley says this:

He goes on to say that Enoch alone was so well read and studied by early Jews that one can find elements of Enochian concepts all throughout the Gospels themselves. Furthermore, Charlesworth continues by saying that ‘many authors of Pseudepigrapha believed they were recording God's infallible words. Early communities, both Jewish and Christian, apparently took some Pseudepigrapha very seriously’ (3). And Enoch and Jubilees were at the top of the list.

Once again, this does not prove Staley’s original assertion that such literature was considered by the early Jews and Christians to be “Holy Scripture.” But what else can we say about the influence of 1 Enoch among early Jewish and Christian communities, including the New Testament authors?

First, though some Jewish communities, like the Qumran community, certainly did hold the pseudepigrapha as religiously significant and authoritative, this could perhaps be compared to some rabbinic views of the oral Torah. Orthodox Judaism claims, for instance, that at least portions of the oral Torah were given to Moses on Mount Sinai and passed down from generation to generation. The oral Torah is therefore considered to have a divine authority in Orthodox Judaism, but no Jew thinks of the oral Torah as being the same as Scripture. In the same way, communities such as the sect at Qumran valued the pseudepigrapha as divinely revealed but not as Scripture.

Contrary to the Qumran Community, the New Testament authors did not consider 1 Enoch to be a source of divine revelation and authority. One reason is that much of the teaching contained in 1 Enoch is directly contrary to the teaching in the New Testament. It is beyond the scope of this article to go into detail, but I outline one extremely important conflict between 1 Enoch and the New Testament in my article, “Who is the Son of Man in 1 Enoch 71:14?”

Obviously 1 Enoch was a religious text that was meaningful to certain smaller sects of Judaism in the Second Temple era, but that doesn’t mean that the New Testament authors valued it as such. The apostles’ use of 1 Enoch can be compared to other instances where they used extra-biblical material that was meaningful to their contemporary audience. As Heiser explains in the quote above, their use of this extra-biblical material does not require that they believed the material to be inspired. It would be like a pastor today quoting a popular movie. A movie might teach meaningful lessons that align with biblical values and theology, but nobody today believes movies are inspired. In the same way, the apostles certainly could have alluded to, or even quoted from, 1 Enoch—emphasizing the parts of it that are true or relevant to their point—without believing in all its teachings or considering it inspired.

Staley continues:

Although some argue that there is ‘no evidence’ that any Christians or Jews considered Enoch or Jubilees or any other Apocrypha books Scripture and that the biblical canon was closed long before Christ, this is a misleading statement. Yes, it is true that the Hebrew canon was most likely closed long before Christ, but that did not mean that everyone agreed in those decisions as the historical record clearly bears out. There were much flux and debate for centuries afterward on this very subject.

Perhaps not everyone did agree about whether the pseudepigrapha should be considered Scripture, but Staley needs to provide evidence for this so we can consider it. That was my original request. I gave four reasons to demonstrate that the Hebrew canon was already established and widely acknowledged among the Judaisms of the Second Temple era, as Staley himself admits. According to the evidence, this widely acknowledged Hebrew canon excluded the pseudepigrapha before, during, and after the time of Messiah.

Staley continues:

For example, there are many Church Fathers that quoted from Apocrypha books. This fact shows that some within the early Christian Church gave at least some of the Apocrypha some sort of authority. No one quotes a source that they don't believe has strong merit or is not authoritative. It doesn't make them correct in their assessment, but it does show us how early Christians looked at those texts.

Staley goes on to speak to issues related to canonicity in regards to the Apocrypha. But this has nothing to do with his original statement that pseudepigrapha, such as Jubilees, “was at one time considered Holy Scripture by many of the early Jews and Christians.”

I am not sure why Staley is talking about the Apocrypha when that was not the topic. Perhaps his point here is to demonstrate that there was disagreement over the canon in regard to the Apocrypha throughout Church history? Nobody disagrees with that. But this does not necessitate that Yeshua or the apostles considered the Apocrypha Scripture. As Beckwith points out, the inclusion of various Apocrypha in the canon of the early Christians “was not done in any agreed way or at the earliest period, but occurred in Gentile Christianity, after the church’s breach with the synagogue, among those whose knowledge of the primitive Christian canon was becoming blurred.”[9] Nevertheless, the issue is not in regard to the Apocrypha but the pseudepigrapha.

Staley continues:

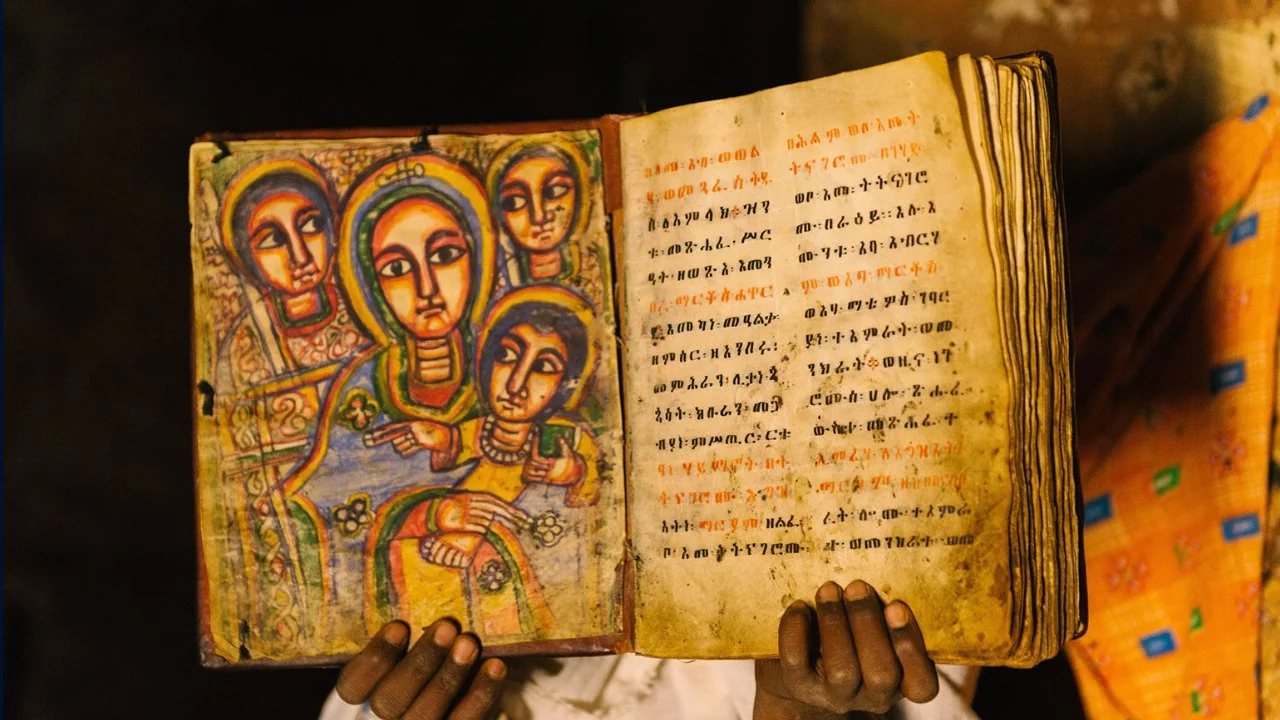

Furthermore, the Ethiopic Church still considers to this day the books of Enoch and Jubilees as authoritative and canonical. This fact doesn't validate those books as such, but does demonstrate that there are groups that did and still believe in their divine inspiration.

Staley is correct that the Ethiopian canon includes 1 Enoch and Jubilees, which makes the Ethiopian church the only Christian community that holds these writings in such a high regard. But apparently the Ethiopian Church has a much more liberal and fluid concept of “canon” than we do. As Roger Cowley writes, in Ethiopia “the concept of canonicity is regarded more loosely than it is among most other churches.”[10] Daniel Assefa, professor of Scripture and Rector of the Capuchin Franciscan Institute of Philosophy and Theology in Addis Ababa, writes:

One can say that Enoch and Jubilees are in the canon, although we need to be careful in our use of the term canon. The concept of canon is not as rigid as in the West. You have various lists and no one seems to be worried or to be preoccupied to have something definitive or normative.[11]

Emmanuel Fritsch, an expert on the Ethiopian liturgy, writes:

My understanding is that there is no canon in the generally received sense; rather, there are various codices which include various books, not always the same, and the same names do not always indicate the same contents. It follows that I would not speak of a canon but of lists of books, lists which do not point in themselves of the nature of the reception of the various writings listed.[12]

Interestingly, while 1 Enoch and Jubilees are included in some “lists” of the Ethiopian canon, they are excluded in others. As scholar Leslie Baynes points out,[13] in A Short History, Faith and Order of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, produced by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church Holy Synod in Addis Ababa, 1 Enoch and Jubilees are not included at all in its list of the “Holy Books of the Old Testament.”

In summary, the inclusion of 1 Enoch and Jubilees in the Ethiopian canon is interesting, but it does not prove Staley’s original assertion that Jubilees “was at one time considered Holy Scripture by many of the early Jews and Christians.” Only the Ethiopian canon includes Jubilees and 1 Enoch in its canon, and their concept of canon is fluid. Furthermore, apparently not all texts included in their canon hold the same level of authority. They have all of these sacred texts, ranging from books they definitely consider holy and of the highest authority, like the gospels, down to early theological commentaries, which are of some authority but generally considered a different kind of authority than Scripture proper. This could perhaps be compared to how the Apocrypha is viewed within Eastern Orthodoxy—while it is considered part of their canon of Scripture, it is generally considered to be of somewhat lower authority than the rest of the Bible.

Staley continues:

Today we have a highly defined group of manuscripts that fit nicely into these named categories that WE created for OUR convenience. It was not so tidy in the days of antiquity; there was much debate on what was to be considered inspired.

Okay, then where is the evidence that any of the Jewish or Christian believers of the Second Temple era considered the pseudepigrapha inspired as Scripture is inspired? Staley goes on from here to talk about the Apocrypha again for some reason, but that doesn’t have anything to do with the topic.

Bottom line? The process of canonization was a tedious process that evolved over a very long time and even when it was "canonized," not every Jewish or Christian sect agreed. To believe otherwise is to be naive to the inner workings of both Judaism, early Christianity, and human nature itself. It was a very messy process; divinely inspired, I believe, but a mess nonetheless.

Staley still has not given any evidence that early Jews and Christians considered the pseudepigraphical literature Scripture.

In the end, I personally completely support the 66 books of what we call the ‘Bible’ (the Book). None other can truly be called ‘inspired’ as Yeshua Himself validates the OT canon from His own words (Luke 24:44). But I also believe, like many of the early Jews and Christians, that there is much to learn from the Apocrypha and other extra-biblical books. But I will agree with the early framers that believed those works should only be reserved for the mature who are already so familiar with the inspired Writ that other parallel works could be digested as a healthy supplement.

Staley’s conclusion appears to disagree with his own original assertion. He agrees that Yeshua validates the OT canon, which excluded the pseudepigrapha. Regarding the rest of his statement, sure, we can glean valuable insights from extra-biblical writings, but only when we appreciate them for what they are. When we make literature such as the pseudepigrapha more than what it is, like Staley did in his first article when he suggested that early Jews and Christians considered it Scripture, we mishandle it and run into error.

In conclusion, Staley appears to be moving the goalposts in his article. He pretends to defend his original assertion but spends the entire article arguing a different point that was never in dispute. And then he concludes his article by agreeing with me that the canon Yeshua affirmed excluded the pseudepigrapha. If his position has changed, he should just admit it. If he still believes his original assertion, then he needs to give evidence for that position.

[1] Jim Staley, “The Real Power of Shavuot,” www.staleyfamilyministries.com (accessed 7/7/19)

[2] Jim Staley, “Public Challenge,” www.staleyfamilyministries.com (accessed 7/7/19)

[3] Roger T. Beckwith, The Old Testament Canon of the New Testament Church, p. 111

[4] Josephus, Against Apion 1.7f., or 1. 37-43; Thackeray’s translation, corrected.

[5] This number is obviously different from the number of books we have in our current Old Testament canon, which is thirty-nine books. The reason for this is that Josephus’ canon combined certain books that are separated in our current canon. For instance, Ezra and Nehemiah were originally one book. Lamentations was likely attached to Jeremiah, Ruth with Judges, and so on.

[6] Beckwith, p. 365

[7] Ryan White, “Should I Study the Book of Enoch?,” www.ryanwhiteonline.com (accessed 7/7/19)

[8] Dr. Michael Hesier, “What’s Ugaritic Got to Do with Anything?” www.logos.com (Accessed 7/7/19)

[9] Beckwith, p. 436

[10] R. W. Cowley, “The Biblical Canon of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church Today,” Ostkirchliche Studien 23 (1974): 318-23

[11] Cited in Leslie Baynes’ essay, “Enoch and Jubilees in the Canon of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church,” A Teacher for All Generations :Essays in Honor of James C. VanderKam Vol. 1, pp. 801-802

[12] Ibid., p. 802

[13] Ibid., p. 803

About David Wilber

David is first and foremost a passionate follower of Yeshua the Messiah. He is also a writer, speaker, and teacher.

David’s heart is to minister to God’s people by helping them rediscover the validity and blessing of God’s Torah and help prepare them to give an answer to anyone who asks about the hope within them (1 Peter 3:15)…